Visit

The Official Web Site of the State of South Carolina

The Official Web Site of the State of South Carolina

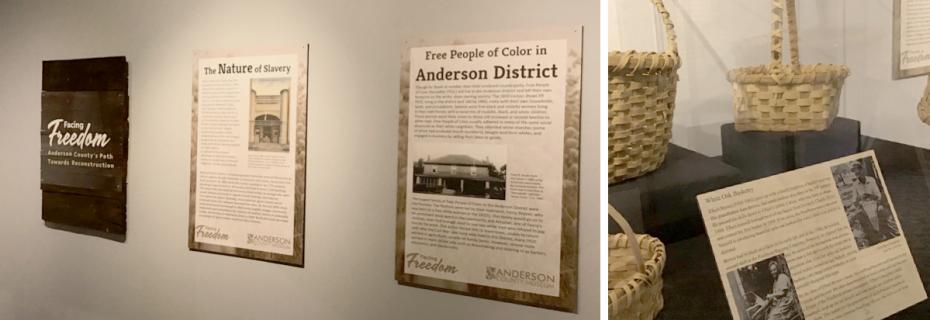

“Facing Freedom” was a temporary exhibit at the Anderson County Museum in early 2020. We hope that you’ll come visit to learn more about the story.

This exhibit makes use of a wealth of first-hand evidence to illuminate the experience of Anderson County’s black population between 1850 and 1868.

This time frame encompasses the immense changes that occurred from the antebellum period of American slavery, through the Civil War, and into the crucial first years of the Reconstruction Era. How did African Americans in our area adjust to life as free people? What did interactions between black and white citizens look like before and after Emancipation? What role did the US government and the Freedmen’s Bureau play in assisting Anderson’s freed people? Facing Freedom investigates answers to these and other topics that helped to define the African American experience for decades that followed.

When Anderson County was first carved out of the Upstate in 1826, slavery had long been present in the area. Some of the largest slave holding families from Pendleton District, and later Anderson County, included the Maxwells, Earles, and Calhouns. Robert Anderson, the Revolutionary after which our county was named, owned slaves on his plantation opposite Andrew Pickens’ famed Hopewell plantation on the Seneca River. Indeed, slaveholding became a firmly established way of life, encouraged by agricultural innovations that made profit all the more possible by the 19th century.

In addition to its economic advantage to white land owners, slavery as a system was reinforced religiously, socially, and politically. Many of South Carolina’s enslaved population had either entered the country as African captives through Charleston, or were born into slavery, descended from those ancestors. By 1860, Anderson County’s population was 37% enslaved, equating to approximately 8, 400 people who lived in about 1,200 dwellings. This meant that each dwelling held two to three families on average who were usually allotted a minimum in regards to food, clothing, and medicine.

Even before the nation’s founding, voices came out against slavery which eventually drew a line between slave and free states. By the mid-1800s those voices would grow loud enough to affect some tangible changes. Abolitionist movements were emboldened by instances of rebellion, stories of unbearable cruelty, and the lives of freed black citizens in both North and South who lived as examples of what freedom could look like in America.

Though far fewer in number than their enslaved counterparts, Free People of Color (hereafter FPOC) did live in the Anderson District and left their own footprint on the white, slave owning society. The 1850 Census shows 99 FPOC living in the district and 160 by 1860, many with their own households, lands, and occupations. Several were free black and mulatto women living in their own homes with a racial mix of mulatto, black, and white children. These women were likely wives to those still enslaved or second families to white men. Free People of Color usually adhered to many of the same social structures as their white neighbors. They attended white churches (some of which had enslaved church members), bought land from whites, and engaged in business by selling their labor or goods. The largest family of Free People of Color in the Anderson District were the Peytons. The Peytons were led by their matriarch, Fanny Peyton, who was born to a free white woman in the 1790’s. This family would go on to be prominent brick layers in the community and Amaziah, one of Fanny’s children, even had enough clout to sue two white men who refused to pay him for his work. This action forced him to leave town, unable to return until after the Civil War. Like most who lived in the District, many FPOC worked in agriculture, usually on family farms. However, several more worked in more skilled jobs such as dressmaking and tailoring or as barbers, mechanics, and blacksmiths.

With each new state to enter the union, slavery became an increasingly volatile issue of debate. The Compromise of 1850 prevented a split as California became a free state, but it served as a shaky scaffolding holding up an impossible load. By 1860, the political temperature had risen such that all it needed was a spark to erupt; a spark that came with the election of Abraham Lincoln.

The bloodiest war in American history ensued between 1861 and 1865. Anderson County men from all walks of life volunteered to fight, some in defense of their homes, or their state, and others in defense of their politics and business interests. For those at the top of the ladder, an end to slavery would mean an end to free labor. For those at the bottom, it may have meant leaving their homes and families to the mercies of Northern occupiers. But for everyone in the South, losing this fight meant an upending of the social order between the races and fears of the consequences that may bring.

South Carolina lost 23,000 men during the Civil War, 560 from Anderson County. The loss of life in addition to those who returned with crippling injuries left many areas of the South in a state of limbo following the war. Economic progress halted and in some cases regressed while the economy shifted away from slave labor. At the same time, infrastructure needed rebuilding having been destroyed by Northern campaigns like Sherman’s March to the Sea. Anderson was no exception as it ceased railroad construction, suffered in the waning agricultural market, and struggled to restore its businesses and trampled farmland. One of the main strategic bodies in helping rehabilitate Southern society, and promoting freed slaves as integral to that rehabilitation, was the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands established in 1865.

Anderson County narrowly escaped the total destruction characteristic of Northern raids which followed the Civil War’s end. However, violence became a part of the new normal as bitterness festered between the South’s many societal factions. Violence took a number of forms including incidents between black and white, ex-confederate and Union forces, within domestic disputes, and in mob settings.

The most documented clash between ex-confederates and Union soldiers occurred at Brown’s Ferry. Southern resources were often confiscated by US officials as having been the property of the defeated Confederacy, though this was not always justified. A load of cotton was seized under murky premises, held at Browns Ferry and guarded by three Union soldiers. The men were found dead on October 9th, 1865, and a trial commenced that consumed the statewide media. James Crawford Keys, his son Robert Lewis Keys, Elisha Byrum, and Francis Gaines Stowers were all on trial, but public outcry against what was seen as an overstep by the federal government resulted in their pardoning by President Johnson.

Manse Jolly himself had been suspected as an accomplice in the Brown’s Ferry incident, but then, he was suspected in most any case where a Union soldier’s life was taken. Jolly had several documented run-ins with the occupying law, but not as much attention is paid to his attacks on African Americans in the folklore. Jolly was listed on a May 23, 1866 outrage report after knocking Priestly Ware down with a pistol. Ware (African American) had a “scalp wound on head” but there was no loss of life in the case.

Mob violence provided a brutal outlet for anger throughout Reconstruction and into the Jim Crow Era. Freedmen and their allies were regularly targeted by whites in isolated attacks or even public lynchings. Extralegal forms of “justice” served to influence local politics, scare individuals or families into leaving town, discourage and prevent Republican votes, and even to control media exposure. In one Anderson County case, a mob stormed the post office to try and retrieve a copy of the New York Tribune they believed was to be delivered.

In addition to militarily occupying the District and rebuilding the southern economy, the Bureau often had its hands full intervening in domestic disputes, building new social guidelines, and financially assisting destitute and starving black and white Andersonians. The Bureau issued thousands of rations to those too poor to feed themselves including widows with children, the elderly and the disabled. Additionally, those too poor to travel had their expenses covered, while elderly Andersonians were many times sent to be closer to family who could support them, often out of state. The Bureau even purchased coffins for the deceased who could not afford funeral costs.

Domestic disputes between whites and the formerly enslaved, and also those within households were investigated by the Bureau. One such case in which the Bureau intervened was that of a Freedman named Jackson. After a fight, his wife stated “she would have put an axe through his head,” and then disappeared with their children that same night. Jackson’s employer, Thomas Anderson, requested that Bureau agents track her down and return the family. Whether or not they did so successfully is unknown. Another case of note is that of Clara Ann Adams. While living on her uncle’s plantation during the war, she had a relationship with and eventually bore a child with Mayne Donalds, an enslaved worker. After the war she wrote to the Bureau asking for assistance because her family cut off support and no one would hire her due to the child.

The Freedmen’s Bureau also helped to establish the first public school for African-Americans in Anderson. Prior to the War, enslaved African-Americans were not permitted to learn how to read or write. With the war’s end, northern missionary societies supported by the Freedmen’s Bureau established thousands of schools for Freedmen across the South. Anderson’s first, called Freedmen’s School No. 1, was likely located on University Hill where the Union soldiers occupying Anderson were usually based. Its first teacher was Private Lewis Phillips of the 1st Maine Volunteers, a Methodist minister before the war. The second school, established shortly after, was the Anderson Presbyterian Sabbath Schools Auxiliary for newly freed African-Americans. This school was taught by Andrew O. Norris, a local white leader who had actually owned ten enslaved people before the war. By 1867 more than 15 schools and Sunday schools for African-Americans had been established across Anderson District with locations in Anderson Court House, Belton, Varennes, and others.

One of the largest challenges facing the Freedmen’s Bureau and the thousands of newly freed African-Americans were the allocation of jobs and homes. These new citizens often had no property, no income, and many were illiterate. The Bureau began working on this massive problem by drawing up contracts between the formerly enslaved and the families who had been their masters.

Often times African-Americans continued to live and work on the same plantations they had their entire lives. Men and women signed contracts to work for their former masters on a yearly basis, usually in exchange for lodging, clothing, or a portion of crops, though some were also paid in cash. Many younger free people, usually girls or boys under 16, were apprenticed out by their parents to learn trades or to work as house servants.

All citizens, both black and white, were penalized for breaking contracts, though the exact terms often differed by landowner and situation. For example, one formerly enslaved man named Calyer Ward worked for his former masters as a mechanic, fully owning half of the shop he worked at on their plantation and making half of its profits while also living in lodging provided by them.

It is possible to witness the progression of black education and society in the district through early working contracts. In the earliest contracts, many black workers simply signed their names with X’s and several did not claim surnames. As the contracts progressed into 1867 and 1868, significantly more black workers had chosen surnames, could personally read the terms of their deal, and sign their own signatures.

As 1868 came to a close, so did the Freedmen’s Bureau. Overwhelmed with often hostile Southern populations that did not support their presence and a government at home that had grown tired of war and occupation, the Freedmen’s Bureau closed its offices in 1868. However, the school program continued until late 1870. Even after the end of the program, many of the schools established by the Bureau across the region continued albeit under different names or in different forms.

The Bureau’s contract system directly impacted the next stage of southern history by creating what would become the share-cropping system. The contracts allowed for the creation of many small farms leased by black farmers and owned by white landlords. In this arrangement, a large portion of all crop yields went to the landowner. A revolving cycle resulted in which share-croppers worked in hopes to build enough wealth to buy out their own farmland, but their work could not yield enough profit to support that vision. This system continued on in the South for more than another century and has had lasting impacts to this day.

This post is an excerpt from “Facing Freedom,” a temporary exhibit at the Anderson County Museum in early 2020. We hope that you’ll come visit to learn more about the story.